Fr. John’s List of the 20 Greatest Films of All Time

When looking at this list, please remember that a color film is not necessarily better than a black-and-white film – you might be surprised. Also remember that a “silent” film merely refers to a film without synchronous sound (such a voice or sound effects). However, most “silent” films have constant music throughout, and some of the best film scores have been written for so-called “silent” films. Also, remember that an “old” film can, in fact, be better than a “new” film. To take an example from the art world: Da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa,” is a very old painting but is still considered to be much better than most (if not all) painted portraits done in our own century. The same standards can be applied to cinema.

When available, both the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) Rating and the USCCB (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops) Rating have been provided. Remember that the MPAA Rating (G, PG, PG-13, etc.) is voluntary. Some films are not rated simply because they were never submitted for a rating.

My rating for all of these films is five stars -- a masterpiece.

1. Citizen Kane (1941)

Length: 119 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG. USCCB Rating: A-II. Director: Orson Welles. Black-and-white.

Considered by many to be the greatest film ever made, Citizen Kane was crafted by a very young Orson Welles and is a loose re-telling of the life of William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper tycoon. The movie is a motion picture masterpiece and is often the centerpiece of many introductory film classes in universities throughout the world. Two times the American Film Institute published a list of the greatest American movies, and both times this film headed the list at the number one position. In a way, it disappoints me to place this film at number one on my own list. Most cinephiles enjoy touting the excellence of some unknown film – one they can call their “own.” However, unfortunately for me, there is no film that I have ever seen that is better than Citizen Kane, so therefore it must be placed at the top. One of the reasons is its perfection from the first day of its release. Unlike many other films on this list, there is no alternate version, restored version, extended version, improved director’s version, or any other version. There is only one Citizen Kane, only one, and it remains completely unaltered and unchanged from the first day of its release until now. And its direction, editing, cinematography, sound design, and sound editing are so perfect as to be examples of moviemaking excellence for generations. Best of all, its brilliant writing makes it entertaining, far more entertaining (and even more “fun”) than most other dramatic motion picture masterpieces. Considered by many to be the most perfectly edited and best-directed film ever made, Citizen Kane is a classic that is not to be missed.

2. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

Length: 82 minutes. MPAA Rating: not rated. USCCB Rating: A-11. Silent with English subtitles. Director: Carl Dreyer

Mercilessly chopped up in sloppy re-edits by those who had no respect for Dreyer’s work and thought lost until a pristine (and properly edited) print was discovered in a closet in a Norwegian mental institution (yes, you read that correctly), The Passion of Joan of Arc is a stunning masterpiece with innovative camera techniques almost unknown in the silent era (including the pervasive closeups of actors who wear no makeup). The resulting footage is a film that floats amidst all time periods – a film of one century ago that looks like it might have been filmed yesterday – a film filled with closeups of wrinkled and freckled faces that provide a timeless and visceral experience. Renée Falconetti plays Joan in what has been widely hailed as the greatest performance ever captured on film. The best version of this work is the gorgeous, properly-restored print available from the Criterion Collection. It features music from the beautiful Voices of Light, a 1980’s composition by Richard Einhorn. This man was so inspired by the film that he wrote this oratorio that plays along with the movie. The bell you hear in Einhorn’s music is an actual recording the composer made of the bell at Joan of Arc’s parish church in Doremy, France. Andrei Rublev (Number 4 on this list) has more content and Napoleon (Number 5 on this list) has more sheer spectacle, but this film, like Citizen Kane, has no missteps at all and is about as perfect as a film can get. And the performance of Renée Falconetti is unforgettable. As Roger Ebert once said, “To see Falconetti in Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc is to look into eyes that will never leave you.”

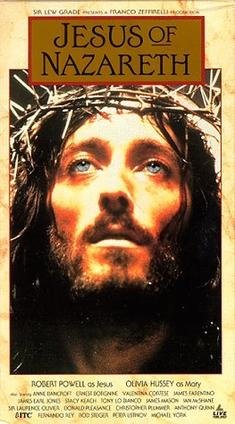

3. Jesus of Nazareth (1977)

Length: 382 minutes. Not rated. Director: Franco Zeffirelli

Made originally as a mini-series for television, this six-hour epic re-telling of the life of Christ is quite possibly the best of its kind that has ever been done. Helmed by famed opera and film director Franco Zeffirelli, Jesus of Nazareth has notable music by famous film composer Maurice Jarre and beautiful cinematography. It is also the product of thorough research; the production team brought in consultants from the Vatican, a noted Rabbinic school, and even a Moroccan Koranic school.

Most importantly, and what takes this film to the level of a masterpiece, is the superb acting. To say that this work “features an all-star cast” would be a gross understatement and would entirely miss the significance of this unprecedented assemblage of talent. Though unknown to many of today’s young people, the men and women who star in this film represent the height of mid-20th Century cinema. Just about every actor and actress, even those in bit parts, commanded top billing in other films with many reaching the status of legend.

The first hired, it is said, was Sir Laurence Olivier. Famous star of stage and screen and knighted by King George VI, this legendary director and actor of Shakespearean films and plays was an old man when approached for this miniseries. He asked simply to be given something “small, like Nicodemus”. He was given that role, and then it became easy to attract other notable legends to the project. Claudia Cardinale, the best-known Italian actress of the time and star in Fellini’s 8 1/2, was cast in the tiny part of the adulterous woman (with only a single scripted line for her to say). Yorgo Voyagis, famous actor hailing from Athens, Greece, took on the role of St. Joseph. Sir Ralph Richardson, yet another knighted Shakespearean actor and co-director of the Old Vic company, took on the small but significant role of Simeon. Others were brought on board – the result being the most illustrious and talented cast of actors and actresses ever assembled for a single film – an astonishing list of acting excellence that has never been matched, before or since.

This list also includes Anne Bancroft, Ernest Borgnine, Valentina Cortese, Donald Pleasance, James Farentino, James Earl Jones, Stacy Keach, James Mason, Christopher Plummer, Anthony Quinn, Rod Steiger, Peter Ustinov, Michael York, Olivia Hussey as Mary, and Robert Powell as Jesus.

The last actor, Powell, was a virtual unknown and the last to be cast. Other possibilities for the role, such as Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino, were quickly set aside in favor of this thin, Lancashire-born man with the distinctive voice. It is considered to be one of the best portrayals of Jesus ever put on film.

Just as gulping a fine wine causes one to miss the delicate flavors, so, too, “binge watching” this mini-series ruins the appreciation of the often-subtle acting and directing. It is best to view this fine cinematic wine a little at a time – for example, one hour a day for six days, in order to truly appreciate its artistry and to leave time for reflection. A cinematic triumph that is not to be missed.

WARNING: The Artisan DVD version is complete. The Shout Factory version and some other DVD and Blu-ray versions (including versions streamed on-line) cut out important scenes such as Judas leaving the Last Supper and Peter insisting to Jesus that he would never deny him, and other scenes. To see the complete, uncut version, view the Artisan DVD version.

4. Andrei Rublev (1966)

Length: 183 minutes (the preferred director’s cut). MPAA Rating: R. USCCB Rating: A-II. Has scenes of violence and torture (though not nearly as intense as film violence in our own day), and one scene with brief nudity. This is not for children. Director: Andrei Tarkovsky. Black-and-white, with color at the end. In Russian with English subtitles.

This lengthy film follows the life of famed Russian iconographer and monk Andrei Rublev as he seeks to come to terms with the sins of his past and hopes, one day, to return to painting (“writing”) icons. Part fact, part fiction, the film nevertheless places you in Medieval Russia like no other film has done before or since. Featuring violence and temptation as well as religious messages, Andrei Rublev is a virtual kaleidoscope of human experience and human life, taking the viewer through the sordid realities of worldly existence and transfiguring the soul in a spiritually uplifting conclusion. The episodic structure, which seems to meander between unrelated events, has been criticized by some. But it is actually very true to life, as most of our lives, if you think about it, follow the exact same pattern – events that may not be directly related to each other but nonetheless find a common thread in the dramatic temporal unfolding of our own existence.

This masterpiece is considered by many, including myself, as one of the greatest films ever made. The Vatican has included this film on its list of the greatest movies of all time.

Suppressed by the Soviet Union and seen only in severely truncated versions during the 1960’s and 1970’s, Andrei Rublev finds its one true home on the Criterion Collection Blu-ray. Many years ago I fell in love with the 205-minute cut which was available on DVD. But the 183-minute cut, available on Criterion Blu-ray, is a great improvement. Not only is it the late director’s preferred cut, which he supervised himself (taking out some more violent elements and trimming other unnecessary shots), but the newer transfer preserves the original aspect ratio of 2.35:1 and cleans up many scratches, flecks, dust, and dirt. The transfer is in beautiful HD. The result is well worth the $35 or so you need to pay to purchase this version.

My least favorite shot of the film needs to be mentioned – the shot of the falling horse. It is considered by many to be totally inexcusable (I am one of those people) and even Tarkovsky’s friends said it should have been eliminated. During filming, Tarkovsky used a horse destined for the slaughterhouse, placing it at the top of creaky stairs so he could film it falling and injuring itself during the Tatar invasion sequence. The shot ends with a Tatar running up and pretending to stab the fallen creature – in actuality, Tarkovsky killed the horse himself with a single bullet after filming was “cut”. The audience sees the horse fall and knows that the injury is real and therefore the sequence really “stops” the film in its tracks. The shot is the greatest weakness in the director’s entire opus, which is why this film cannot possibly be number one on this list. Mercifully, Tarkovsky shortened this shot in his preferred cut – an apparent compromise between his desire to keep the shot in and the insistence of so many that it should be eliminated. The shot is there but the trauma of it is greatly reduced.

Despite its very few flaws, Andrei Rublev is a truly spiritual experience and the greatest work of a great director. Though one viewing is sufficient for many people, the film requires more than one viewing to be truly appreciated.

5. Napoleon (1927)

Length: 235 minutes. MPAA Rating: G. USCCB Rating: A-II. Silent. Director: Abel Gance. Black-and-white with hand-tinted footage. The version referred to here (there are multiple versions) is the print housed in the British Film Institute and shown in London in 2004 and in Oakland, California in 2012 with Carl Davis conducting his own score with a live symphony orchestra.

Made back in 1927 as part of a projected six-part series on the life of Napoleon Bonaparte and painstakingly restored in the 1980’s, Napoleon covers only a tiny portion of the conqueror’s life, concluding only with his first entrance into northern Italy. The other films were never made, but this is an amazing achievement, with camera moves and radical editing techniques that were way ahead of their time, including hand-held camera, multiple exposures, rapid-fire editing, smash cuts, multiple images, tracking shots, and so much more. Features passionate directing and acting. For the final scene, Gance uses a primitive form of Cinemascope, taking three movie cameras and synchronizing them together. A showing at a theater features the curtains parting at the final scene, revealing an extra wide screen, at which time three projectors roar to life, showing either a single enormous panorama shot or three separate shots rapidly edited together. The result is quite mesmerizing and one of the most visually inventive sequences in all film history. It also came at a price – the young editor spent weeks in her bed after having suffered a nervous breakdown editing this opus. Loud and enthusiastic standing ovations greet the film on the rare occasions when it is shown (due to the enormous expense of showing it, the film is rarely presented). Technically even more advanced than Citizen Kane, Abel Gance’s Napoleon is a film like none other, and whenever shown is quite literally the motion picture event of a lifetime. I was fortunate enough to be at the 2012 Oakland showing (even though I lived in Boston at the time) and it was most certainly worth flying clear across the country to see this extraordinary cinematic achievement.

Despite the clear technical and artistic brilliance of this work, this film must be placed below such other classics as Jesus of Nazareth and The Passion of Joan of Arc. Why? First off, there are so many versions of this film (well over twenty by now) that it is impossible to say which one is truly the director’s original vision as opposed to being a modernized embellishment. Also, for all its daring do, the subject matter of Napoleon is quite problematic. It canonizes and sometimes even divinizes this tyrant, often suggesting that Napoleon the man was a leader much like Moses, or a divine presence much like Jesus, sometimes literally striking people silent with his glowing and ethereal appearance. The gorgeous cinematography and sweeping camera movements only accentuate the lie, and sequences (restored more recently) showing a young woman constructing a small Napoleon “shrine” in her bedroom so she can swoon over his image elicits mostly laughter from the audience. This takes away from the brilliance of a work that is still a joy to watch and appreciate.

6. Rashomon (1950)

Length: 88 minutes. MPAA Rating: Not rated. USCCB Rating: A-III. Dramatic depiction of rape and murder. The content is very tame by today’s standards but is still not suitable for very young children. Director: Akira Kurosawa. Black-and-white. In Japanese with English subtitles.

The story of a rape and murder is told from four different perspectives. Was it a rape? Was it a murder? As two men wrestle with the maze of conflicting testimonies, struggling to discover the truth, they enter into a deep discussion about the nature of truth itself, and the meaning of life. This film, which put both Kurosawa and Japanese cinema on the map, became so acclaimed that the word “Rashomon” eventually made its way into the vocabulary of law practice (the “Rashomon effect,” in which people contend with the complexities of conflicting testimonies). Despite its dark theme, the film has an ending that is spiritually uplifting and underscores the universal thirst for love and beauty in a broken world.

7. Spirited Away (2001)

Length: 125 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG. USCCB Rating: A-II. Director: Hayao Miyazaki. In color (animated). Comes in two language versions – one in Japanese and one in English.

A true auteur, Miyazaki writes his own stories, writes his own screenplays, draws detailed storyboards for every scene in the film, does some of the detailed animation himself, directs his own films, and even writes song lyrics. He usually begins with one or two images and formulates the story from there. Miyazaki and film composer Joe Hisaishi have collaborated for years on a number of Studio Ghibli films, but this is probably their masterpiece. Often called the greatest animated film ever made, Spirited Away tells the story of a ten-year old girl who is whisked away to a fantastic and often scary land where she must work hard in a spirit bath house and find emotional maturity in order to release her parents from a horrible spell. The music is beautiful, the story is often emotionally overwhelming, and the animation is nothing short of astonishing (both in its scope and in its minute details). When considering Miyazaki is responsible for so much of the filmmaking process, and when considering how unique this work is in comparison to other animated films, there is no question that Miyazaki’s work belongs in the top ten on this list, and Miyazaki himself belongs on any list of the world’s greatest filmmakers.

8. City Lights (1931)

Length: 86 minutes. MPAA Rating: G. USCCB Rating: Not rated. Director: Charles Chaplin. Black-and-White. Silent (with recorded music and a few comical sound effects).

Considered to be one of Chaplin’s greatest masterpieces, City Lights tells the tale of the Little Tramp who falls in love with a blind flower girl. The flower girl mistakes the Tramp for a very wealthy man. If she ever learns the truth, will she fully accept him? The ending is touching – it is said that famed scientist Albert Einstein cried during the premiere.

The film was made at the very beginning of the sound era. Adamant that the Tramp does not talk and convinced that sound would ruin the magic of the character, Chaplin resisted enormous pressure to make a sound film. Not only did Chaplin end up making a silent, he used synchronous sound effects briefly at the very beginning of the film to make a mockery of the new sound technology. Chaplin’s skills as both an actor and acrobat are evident here, as he not only produced, directed, starred and edited this film, but also did so in his very own studio, with actors he cast himself, using a story and script he wrote himself, and some original music he composed as well. All these elements easily send this film into this top twenty list, because very few individuals in movie history have exhibited such a mastery in the medium in so many areas of expertise simultaneously.

9. The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003)

Length: Only extended versions reviewed here: 208 minutes for The Fellowship of the Ring (1st film), 223 minutes for The Two Towers (2nd film), and 250 minutes for The Return of the King (3rd film). MPAA Rating: PG-13. USCCB Rating: A-III. Director: Peter Jackson.

Peter Jackson’s epic cinematic re-telling of Tolkein’s classic trilogy has been called the greatest fantasy trilogy ever made. And it is. Here I count all three films as one film. This is because it is one story and the three films are designed to go together (and seeing any one of the films individually is not a complete experience). Entirely made in New Zealand (including the landmark visual effects) and featuring somewhat controversial departures from Tolkein’s original intent, the films are stirring and often breathtaking. To avoid having to wrestle with contract re-negotiations and other difficulties, Jackson shot all three films back-to-back, making for a very long shoot. Howard Shore’s music is atmospheric and plumbs the depths of the story’s majestic settings. The visual effects push the digital technology of the time to the limit – so much so that no film since has matched this trilogy’s innovation and artistry. The performances should be noted as well, most especially Elijah Wood’s very affective performance as Frodo, Sean Astin’s moving performance as Sam, and Andy Serkis’ iconic and masterful interpretation as Gollum (Serkis deserves almost all of the credit as his facial expressions and body movements provide the blueprint for animating the character).

All this said, the trilogy is not without its weaknesses. Peter Jackson’s reticence to end any of his films is most apparent in the long, drawn-out conclusion to the last film, a weakness that is easily compensated for by the length and breadth of everything that precedes it. Additionally, Jackson’s penchant for sweeping camera movement and dramatic use of wide-angle lenses gets overdone sometimes – but fits in very well in this fantastical setting.

10. Ran (1985)

Length: 160 minutes. MPAA Rating: R. USCCB Rating: A-II. Director: Akira Kurosawa. In Japanese with English subtitles.

Instead of three daughters, there are three sons. Instead of King Lear, there is Lord Hidetora. Other than that, and the obvious re-setting of the action in sixteenth-Century Japan, this is a faithful re-telling of William Shakespeare’s King Lear. Designed over a painstaking ten years and filmed with dozens of extras atop Mount Fuji, Ran (pronounced like the name “Ron,” the Japanese word for “chaos”) is a tour-de-force and most definitely Kurosawa’s last great masterpiece. The Criterion Collection DVD includes a wealth of extras, documentaries, commentaries, a video using Kurosawa’s own preparatory paintings and sketches, and a 28-page booklet on the film and its appreciation. Don’t settle for other DVDs or streamed versions where they “fix” the bright colors to make them look more subdued. Kurosawa wanted bright colors (as you see in the Criterion Collection). The colors are part of the motif of his latter-day films, distilling the moving image into its basic components. Filled to the brim with far shots and almost no close-ups at all, it is clear we are invited to view, at some distance, the chaos (“ran”) of swirling colors and armor as a fable of selfish humanity at war with itself.

11. Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

Length: 68 minutes. MPAA Rating: Not rated. USCCB Rating: Not rated. Director: Dziga Vertov. Silent. Though not morally offensive, some people might be surprised by documentary scenes of brief nudity, a birth, and the body of a young man being carried in a funeral procession. Not for younger children.

Made in the Soviet Union in 1929, Vertov’s masterpiece captures daily life among typical Russians of the early 20th Century. If we see firefighters racing to a fire, they are real firefighters. If we see a wedding, it is a real wedding. If we see a couple filing for divorce, it is a real divorce. The birth we see is a real birth. The funeral procession we see is a real funeral procession. In our age of social media, this may not seem too impressive, but back in 1929 such cinematic insights into everyday life were quite extraordinary.

This documentary has no story, no plot, and no actors. It is, instead, a time capsule – and an astonishing one at that. Vertov’s goal is to de-mystify the process of moviemaking, divorce film from drama and literature, and reveal the inner workings of cinema in order to create a purely cinematic language. He does this by including shots of himself with his camera and, in one memorable sequence, shots of an editor splicing together the very movie we are watching.

Way ahead of its time, Man with a Movie Camera utilizes such techniques as multiple exposures, split screens, dutch angles, slow motion, fast motion, and rapid-fire montage editing – all pretty amazing for a one-hundred-year-old film. Sprinkled amidst scenes of everyday life are messages from the Soviet era that are more generalized and not very political -- for example, it is better to play a game of checkers than to get drunk, exercise is good for health, and machines increase productivity. But at the center of this venture are ordinary people like you and me and our progression through the journey of life. My favorite version of this film can be found on DVD from Image Entertainment and features the unique and somewhat bizarre music soundtrack of Alloy Orchestra, which was composed by carefully following the detailed (and eccentric) notes of Vertov himself. From its slightly-surreal opening sequence to its rapid-fire conclusion, Man with a Movie Camera is experimental moviemaking at its best.

12. The Sound of Music (1965)

Length: 174 minutes. MPAA Rating: G. USCCB Rating: A-I. Director: Robert Wise.

It has no scenes of violence, no cursing or swearing. Above all, it is a family-friendly musical and has a happy ending. These attributes of The Sound of Music are enough to send some film aficionados running to the nearest trash bin, eagerly ready to throw away this film in favor of darker, more violent, and more “serious” fare. Those too quick to judge this family favorite often overlook the obvious – that this is an amazingly well-crafted film, with superb direction, beautiful cinematography, unforgettable music, and very high production values. There is no getting around it (even though some “serious” film fans would desperately want to do so) – The Sound of Music is a great film and probably the greatest cinematic musical ever made. Aware of the popular appeal of musicals as well as the concerns of both Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer that the film would not be too “saccharine,” director Robert Wise strikes a delicate balance between a light-hearted musical and a deeply-felt wartime drama. The balance works. If you think about it, the result is rather unique in the history of movie musicals – a film that is not easily categorized. It is certainly not as dramatic as The Bridge on the River Kwai and is not nearly as light-hearted as Meet Me in St. Louis but falls somewhere in between. Featuring very solid performances by the entire cast, but most especially by the two leads, and some of the most beautiful music ever written for stage or screen. Well worth repeated viewings.

13. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Length: 148 minutes. MPAA Rating: G. USCCB Rating: A-II. Director: Stanley Kubrick.

Kubrick’s most famous and perhaps most mind-bending film takes place in the “future” (the year 2001), when mankind discovers a hidden obelisk on the moon which leads to an unforgettable journey near the planet Jupiter. Considered a masterpiece of visual effects, 2001 features scenes partially designed by Stanley Kubrick but mostly designed by legendary visual effects artist Douglas Trumbull. Wanting to preserve the integrity of the cinematic image in an age when optical printing would have added a lot of noise to the film, Kubrick insisted on careful exposure of spaceship models (sometimes taking an entire day) as well as on rotoscoping mattes (painstakingly slow process of directly drawing on the film by hand – one frame at a time). The result is the first film in motion picture history to present a totally realistic vision of space travel. The slow pace (sometimes crushingly slow) is deliberate and part of the realistic vision. There is no question this is more of an atheistic interpretation of how man became so intelligent – but it is interesting to note that a wise man like agnostic author Arthur C. Clarke saw some sort of outside intervention as being part of the journey of humanity. Instead of God he settles for a super-intelligent monolith-constructing alien race, but the result is somewhat the same (only somewhat) – mankind becomes endowed with intelligence, taking him beyond all other life on earth, and prompting him to reach for the stars.

14. The Apu Trilogy (1955-1959)

Length: 112 minutes for Pather Panchali (1st film), 138 minutes for Aparajito (2nd film), and 107 minutes for Apur Sansar (3rd film). MPAA Rating: Not rated. USCCB Rating: Not rated. In Bengali, with English subtitles. Director: Satyajit Ray. Good for family viewing, though some scenes of family difficulties may be too intense for very young children.

It is often that a movie will fill the eyes and weary the mind. It is less often that a movie will illuminate the mind and fill the heart. But rare is that precious film which enchants the heart and inspires the soul. Such is the case with Satyajit Ray’s “Apu Trilogy,” often lauded as one of the cinema’s greatest and most masterful achievements.

Why it is considered so great is open to debate. Is it simply enthralling for Western man, beleaguered by the burdens of our commercialized society, to view the rich tapestry of life’s simplicity as found in strange and distant India of the mid-20th Century? Perhaps. But praising the film is more than an exercise in lauding an exotic locale. It is a recognition of the true artistic excellence of the man who brought Indian cinema onto the world stage – and dared to bring realism to an Indian movie industry more accustomed to musical escapist fare.

A founder of the Calcutta Film Society, Satyajit Ray was greatly influenced by the works of Wyler, Ford, and Renoir. His first film was Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road), the first of the Apu Trilogy. Strapped for funds, he relied heavily both on the government of West Bengal and a sympathetic voice from New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The resulting footage enthralled the audience at Cannes and went down as one of the greatest “first films” ever made.

Based on the novel by Bibhutibhusan Banerjee, Pather Panchali tells the story of Apu (Subir Banerjee), a bright-eyed boy beginning his life in early-twentieth-century rural India. Living with their aging “auntie” and their hardworking parents, Apu and his sister Durga celebrate their youth and celebrate life. Food, including nourishment that is shared with others, becomes an important part of this celebration.

Apu’s world is soon turned upside down. Sickness and death assert themselves. The family continues its journey through life in the next film, Aparajito. Now Apu is a teenager. Buffeted by both adventure and tragedy, the young Apu delves into books and intellectual development. Now food for the mind becomes a celebration – it is now chalk, slate, books, and papers which look nourishing. Apu here is not a teen idol but a real teen – awkward, questioning, and struggling on his journey to adulthood.

The third and final film, Apur Sansar, takes a partially comedic look at the life of the young man Apu, who struggles to understand what it means to be a good man and a good husband. The end of the film, and thus the conclusion of the trilogy, is a spiritually transformative scene that touches the heart with the promise of a better and hope-filled tomorrow.

In this amazing trilogy, the shots are long and the reaction shots are longer. But there is no wasted footage here. Nothing is forced. Each shot, perfectly composed, pours generous amounts of truth and nature into our souls. A great deal of ambient sound, lush visuals of natural surroundings, and tender closeups of tender faces are enriching and illuminating. No director commands our attention on the natural level as much as Ray does here. Simple foods have never seemed so delicious, sicknesses have never seemed so burdensome, youthful adventures have never seemed so hope-filled, and people have never seemed so real. It is as if the rest of cinema is a game of “let’s pretend,” with Ray’s Trilogy providing the best and most accurate barometer of what is truly immersive cinema.

15. The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Length: 101 minutes. MPAA Rating: G. USCCB Rating: A-I. Director: Victor Fleming.

We’ve all seen it, and we all love it. Forget about the behind-the-scenes difficulties, the strike by the “munchkin” cast, or a Judy Garland who was clearly too old to play the young Dorothy (Shirley Temple was initially considered for the role). It all works brilliantly. The transition from black-and-white to color is still one of the best transitions in the history of cinema. The music is delightful, the cinematography is beautiful, the sets and costumes are quite impressive, and even the effects hold up well (the tornado is still perhaps the best tornado in the history of cinematic visual effects). The mostly song and dance cast is extremely talented – this includes Margaret Hamilton, whose Wicked Witch doesn’t sing or dance but tears up the screen with a still-effective villainous performance. This is a family classic that can be enjoyed by all ages.

16. Metropolis (1927)

Length: 148 minutes. MPAA Rating: Not rated. USCCB Rating: Not rated. Director: Fritz Lang. Silent, with music (original score by Gottfried Huppertz).

Not for very young children, but okay for adolescents and older.

Imbued with operatic acting and some impressive visual effects, Metropolis is a grand sci-fi pageant that underscores the struggle between the rich and the poor, the elites and the servants, the haves and the have nots. Whether it’s the workers who trudge out from the factory precisely at half the speed of workers just arriving, the men straining to complete another grueling ten-hour shift by mindlessly operating meaningless controls, or a machine so large it appears to devour those who serve it, virtually every shot is layered with social commentary.

The favored son of the leader of Metropolis, Freder is fully satisfied with his privileged existence until he meets the angelic Maria, a latter-day prophetess from the world below. Felt moved to truly understand the other side, Freder travels below and trades places with one of the workers. What follows is a drama that becomes increasingly exciting, even frantic, featuring a rebellion, deception, a mad scientist, a golden robot, and some of the most spectacular visual effects of the silent era (Germany was the world leader in cinematic effects at that time).

In case we don’t get the point, Lang includes some interesting spiritual/religious references. The large devouring machine is called “Moloch,” a reference to the horrifying temple of child sacrifice found in the Old Testament. When speaking to the workers, Maria stands in front of an “altar” with several crosses perched overhead. The story of the Tower of Babel is told through dramatic imagery. And when Freder is half-delirious while tossing and turning in bed, he sees sculptures of the Seven Deadly Sins come to life, while, at the same time, the Maria-impersonating golden robot lustfully dances as the whore of Babylon for an audience of wealthy young men all too eager to torch the night with mayhem.

This is an intense, operatic, and melodramatic epic which eschews moderation in favor of spectacle. It sweeps you into its strange, retro world of 1920s sci-fi and doesn’t let you go. Though now nearly one hundred years old, Metropolis still has a freshness and vibrancy that still grabs the viewer. No wonder that such films such as Star Wars, Blade Runner, and countless others have been inspired by its visuals and even appropriated some of its characters and effects. The Vatican has included it on its list of the greatest films ever made, under the category “art”. It is true that the message of the film is a simple one, but there is nothing really simplistic about it. It works for me and stands the test of time.

Find the complete version on the Blu-ray disc from Kino, which includes 25 minutes of restored footage and the sweeping original music soundtrack by Gottfried Huppertz. Yes, it’s a silent film, but there is nothing silent about the visuals. Lang’s skilled direction and the great melodramatic acting make petty things like synchronized dialogue unnecessary. And Huppertz’s mesmerizing and unrelenting music fills in all the gaps. It’s a great film and well worth watching.

17. Ben-Hur (1959)

Length: 212 minutes. MPAA Rating: G. USCCB Rating: A-I. Director: William Wyler.

William Wyler once famously quipped that it took a Jew to finally make a decent life of Christ. He was referring to his own 1959 version of Ben-Hur. There had already been a silent version – very big-budgeted and very well-received. But with the new wide screen formats of the 1950’s, it made perfect sense to make a full color version with the newer and sharper film stock – and wider screen.

But is it a life of Christ? Not really. It is the life of Ben-Hur, a Jewish prince turned slave, turned hero, turned Christian. Ben-Hur’s life is bookended by scenes from the life of Christ, an interesting structure that can be found in the original novel by General Lew Wallace. The Civil War general turned author, irritated one day by an atheistic mocking of Jesus he heard on a streetcar, went home in anger and, with great determination, created the Christ-centered bookends for his novel.

This film works on many levels, including solid performances by a splendid cast, a sweeping score by the masterful Miklós Rózsa, and an unforgettable chariot race sequence that has never been duplicated (the myth persists that extras were killed – this is not true for any version of the story, though a couple of horses were fatally injured during the making of the silent version). This grand epic lapped up a hefty eleven Academy Awards and remains an American classic.

18. The “Up” Series (1964 - 2019)

Length: about 40 to 150 minutes per film, total of nine films. MPAA Rating: Not rated. USCCB Rating: Not rated. Director: Paul Almond (first film only) and Michael Apted (all other films in the series).

It started simply enough as a documentary profiling several English children from a variety of backgrounds. Since all the children were seven years old, the film, made in 1964, was entitled 7-Up, a cute and “hip” nod to the popular soft drink.

But it didn’t end there. Director Michael Apted caught up with these children seven years later, making a documentary to chart their progress into the teen years. Suddenly, a surreal and wholly unique cinematic journey was born, with Apted making a documentary once every seven years, following these very same individuals (now adults) through the joys and sorrows of life, the title of each documentary following the current age of the participants. The series has currently reached the quite astonishing 63-Up which premiered in 2019. Since then, Apted has died, and it is not known if the series will continue.

The result is a dramatic and mind-bending journey through time, with hairstyles, clothing styles, and even film stock changing through the years. The participants experience first loves, broken dreams, devastating losses, and new hopes for the future. Some participants are eager to talk, while others disappear and refuse to participate. Still others find the once-every-seven-years visit of the cameras to be a burden, but a burden that is increasingly easier to carry as a growing appreciation for the whole venture matures over time. In any event, this is, quite clearly, one of the most bizarre and yet one of the most blazingly unique series of documentaries ever committed to film. Viewing these films means watching human lives (real human lives) develop, unfold, and mature before our very eyes – over a period of a half a century. The end result is a masterpiece – and we are enriched by the mystery of life itself.

19. Psycho (1960)

Length: 109 minutes. MPAA Rating: R. USCCB Rating: A-III. Director: Alfred Hitchcock. Not for young children.

This taut and sleek thriller was a departure for Hitchcock when he made it in 1960. The low budget and black-and-white cinematography along with Bernard Hermann’s strings-only score make this Hitchcock’s most seminal work – a film which, unfortunately, ushered in the era of violent and gory slasher films. The irony is that we see very little blood in this film and we never actually see Janet Leigh being stabbed in the shower – the famous montage editing makes us believe we are witnessing much more than what is actually being shown to us. The quirky, unnerving performance of Anthony Perkins carries us into the mind of a true psycho – a journey that is fascinating and disquieting. The final shot, a dramatic multiple exposure with multiple layers of meaning, is by far the most unforgettable final shot in the history of cinema.

20. 12 Angry Men (1957)

Length: 96 minutes. MPAA Rating: Not rated. USCCB Rating: Not rated. Director: Sidney Lumet. Good for family viewing.

This courtroom drama follows the deliberation of an all-male jury as it seeks to determine if a young man is guilty of murder beyond a reasonable doubt. A wide array of American acting talent is presented here – especially noteworthy are the performances of Henry Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, and E.G.Marshall. It is quite a challenge to make a film interesting when all the action is in an enclosed space, but director Sidney Lumet takes the jury room and turns it into an operatic venue. The audience is so immersed in the character study of these angry men that we easily overlook the fact that we are stuck in the same small room for 98 percent of the film’s running time. A great courtroom drama – an American classic.